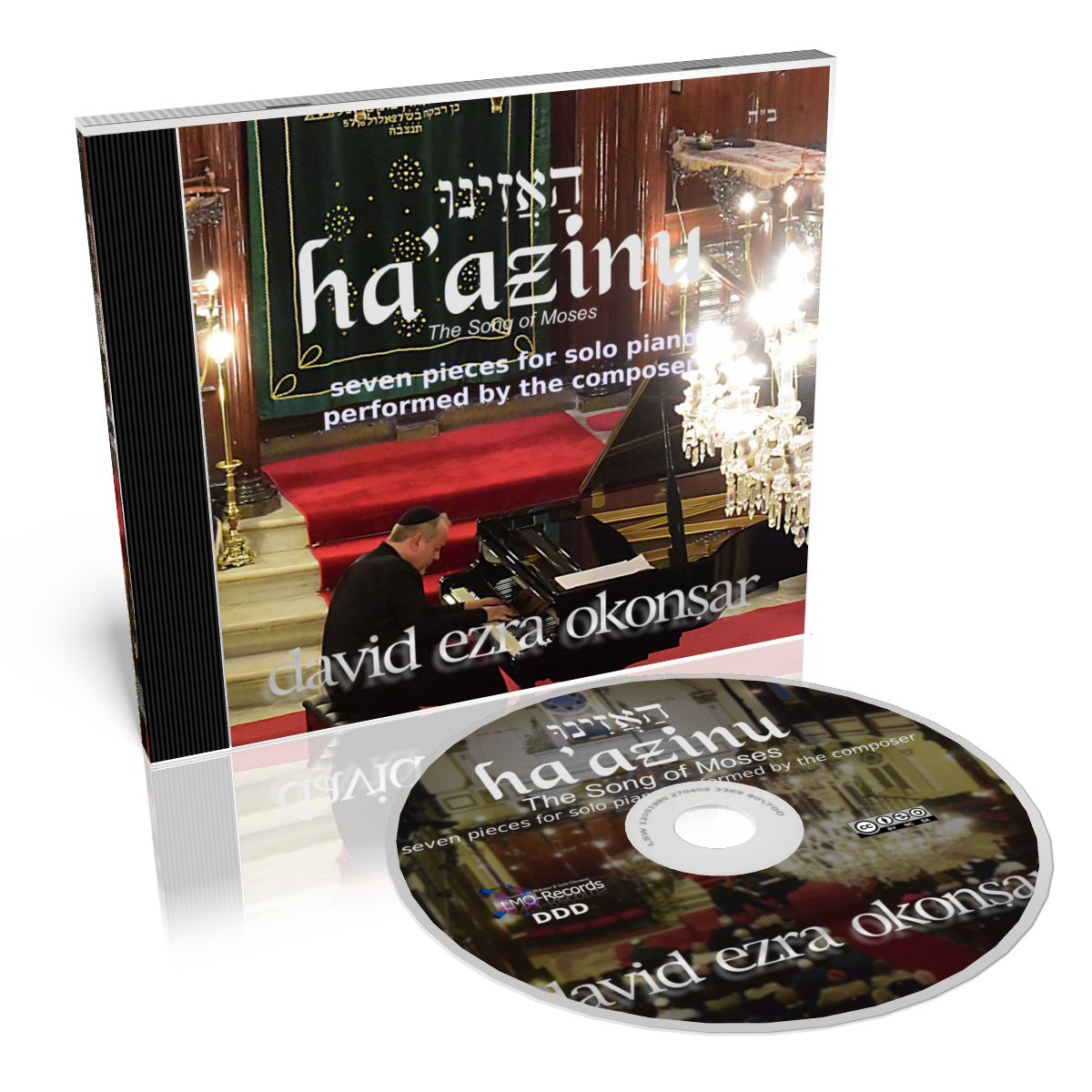

Haazinu (Listen!)

The Song of Moses

Seven Pieces For The Solo Piano

CD

|

The timeless nature and profound poetic elocution of the section from Deuteronomy 32:1-52, known in the Jewish tradition as Shirat Ha'azinu, the Song of Moses, is the source for this series of solo piano compositions. The work is in seven movements, following the seven chapters, aliyah[1], scheme the Ha'azinu is traditionally divided in the Torah portion Parashah[2]. The composition uses dodecaphonic (twelve-tone) series. The note-series are elaborated based on the symbolic significance attached to the musical note-intervals. The poem opens with an exordium, the introductory part of the oration, (verses 1-3) in which heaven and earth are summoned to hear what the poet is to utter. In verses 4-6 the theme is defined: it is the rectitude and faithfulness of G-d towards His corrupt and faithless people. Verses 7-14 portray the providence which conducted Israel in safety through the wilderness and gave it a rich and fertile land; verses 15-18 are devoted to Israel's unfaithfulness and lapse into idolatry. This lapse had compelled G-d to threaten it (verses 19-27) with national disaster and almost with national extinction. Verses 28-43 describe how G-d has determined to speak to the Israelites through the extremity of their need, to lead them to a better mind, and to grant them victory over their foes. Haazinu, the initial word of the Parashah, means "listen!" addressed to more than one person, it is also spelled Ha'azinu or Ha'Azinuּh. It is said that "Moses spoke in the ears of all the assembly of Israel the words of this song" (Deuteronomy XXXI. 30, R. V.; comp. ib. XXXII. 44). The song exhibits striking originality of form; nowhere else in the Torah are prophetic thoughts presented in a poetical form a scale so large. The use of the verbs "listen (!)" and "[let the earth] hear" is extremely subtle. As the Lubavitcher Rebbe Menachem Mendel Schneerson (1902 - 1994) O.B.M. put it: "We use the word “listen,” when we speak with someone who is close. Our conversations with a listener are personal and private. We use “hearing” when we speak to someone further away.[..] Ha’azinu gives an example of both “listening” and “hearing.” Moshe asks the heaven and earth to serve as witnesses, saying: Ha’azinu hashamayim … V’sishma ha’aretz: “Listen, O heavens…, and let the earth hear.”[3] We have here a declamation of such intensity that it encompasses not only both heavens and the earth, but also the very far ("hear") and the very close ("listen"), furthermore not only Moses is addressing to them but he is also calling them, the heavens and the earth, to witness his words. Therefore the speech to follow is simultaneously cast in past, present and future as well as in heavens and earth. Also known as the "Song of Moses" it is a denunciation of the Israelites’ sins, a presage of their punishment and a promise of G-d’s absolute redeem of them. Most of the text appears in the Torah scroll in a special two-column format, in conformity with the poetic structure of it. The Mekhilta[4] of Rabbi Ishmael[5] counted ten songs in the Torah. Among them the "Ha'azinu" that Moses spoke in His last days. Rabbi Samuel ben Nahman[6] asked why Moses called upon both the heavens and the earth in Ha'azinu. He compared Moses to a general who held office in two provinces and was about to hold a feast. He needed to invite people from both provinces, so that neither would feel offended for having been overlooked. Moses was born on earth, but became great in heaven. In next verse: "My lesson {doctrine} will drip {drop} like rain; my word {speech} will flow {distill} like dew", rain and dew are not without analogy with "listen" and "hear". Rain is liquid precipitation, water falling from the sky. It can be beneficial as well as destructive. Dew is water droplets condensed from the air, often at night, on cooler surfaces near the ground, mostly on leaves. Rav Judah and "Rava"[7], inferred from Ha'azinu the great value of rain. Rava also inferred from the comparison in Deuteronomy 32:2 of Torah to both rain and dew that Torah can affect a worthy scholar as beneficially as dew, and an unworthy one like a crushing rainstorm. Through the Bible, rain and dew are words with deep layers of meanings. Dew is a source of great fertility (Gen. 27:28; Deut. 33:13; Zech. 8:12), and its withdrawal is regarded as a curse from G-d (2 Sam. 1:21; 1 Kings 17:1). It is the symbol of a multitude (2 Sam. 17:12; Ps. 110:3); and from its refreshing influence it is an emblem of brotherly love and harmony (Ps. 133:3), and of rich spiritual blessings (Hos. 14:5)[8]. There are three Hebrew words used to denote the rains of different seasons. Both the essential and beneficial aspects of rain are expressed. In: "My lesson will drip like rain" (Deuteronomy Chapter 32:2) that Sifrei[9] comments: this is the testimony that you shall testify, that in your presence, I declare, "The Torah, which I gave to Israel, which provides life to the world, is just like this rain, which provides life to the world, [i.e.,] when the heavens drip down dew and rain." the essential and beneficial aspects are highlighted. This is connected with "my word will flow like dew." That is "with which everyone rejoices, {unlike} the rain {which occasionally} causes anguish to people, such as travelers, or one whose pit {into which he presses his grapes} is full of wine {which is spoiled by the rain}[10]. According to Rav Ezra Bick (from: Yeshivat Har Etzion): [..] Ha'azinu is "shira," a song. Unlike the other songs in the Torah, which fulfill a historical purpose - the Jews really did sing a song of rejoicing after the splitting of the sea, Ha'azinu is a "song on demand": G-d told Moshe to compose the song. One simple question: why? Or, in other words, what is the meaning of a "song" in the context of Moshe's farewell speeches to the Jewish people? First, we have to understand what is the basic theme of Ha'azinu. I think it is fair to say that the basic theme of "shirat ha-yam" (the song of the sea) is praise of God, as a response to the miracle. This is the standard meaning of shira, as a Halachic[11] concept, in general - one utters shira after a great miracle of redemption: Hallel[12]. But clearly, Ha'azinu does not have that character, both by an even superficial internal text reading, and in the absence of a miracle to which the song is in response. In fact, the Torah explicitly and repeatedly defines the nature of Ha'azinu: "And I shall surely hide My face on that day, because of all the evil that (the people) have done, for they have turned to other gods. Therefore ("ve-ata"), write for yourselves this song, and teach it to the Jews to place in their mouths, in order that this song be a witness for me against the Jews" (31,18-19). "And when many evils and troubles shall befall them, then this song shall answer them as a witness, for it shall not be forgotten from their seed..." (31,21). "Gather unto me all the elders of your tribes and your officers, and I shall speak in their ears these things, and I shall call the heavens and earth as witnesses against them; for I know that after my death you shall become corrupt, and leave the way which I have commanded you..." (31,28-29). Accordingly, the opening lines of Ha'azinu: "Listen heavens, and I shall speak; let the earth hear the words of my mouth" are not merely a poetic opening, but represent the crux of the song: a calling of witnesses who will be able to testify when the time comes. The song is to be a future witness, connected to the evil deeds of future generations, and to the evil that will befall them as a result.[13] About the composition: "Ha'azinu: Listen, O heavens, and I will speak! And let the earth hear the words of my mouth!". The first piece starts "quasi niente" ("pppp": as soft as possible). The powerful words that open Haazinu are transcribed here as soft as possible. The movement includes wild contrasts. Very tender lines alternate with strong and resounding chords which also alternate with dry, short and harsh note-clusters. More than once one have the main tone-series deployed as "Moses speech" in either a baritone range or as "reflected from the skies" in very high registers. It concludes again with a polyphony as in the opening, yet this time more dense and built with the deployment of the main series in several ranges simultaneously. The main series of the entire series, used as it is in pieces number one and seven, favors intervals of perfect four and chromatic steps. The P4 interval represents the perfect harmony and the chromatic step, specially downwards has always been the representation of lament and fall. In "Remember the days of old", the second section of the Ha'azinu, Moses exhorted the Israelites to remember that in ages past, G-d assigned the nations their homes and their due, but chose the Israelites as G-d’s own people. G-d found the Israelites in the desert, watched over them, guarded them, like an eagle who rouses his nestlings, gliding down to his young, G-d spread His wings and took Israel, bearing Israel along on His pinions, G-d alone guided Israel. [14] The music is evanescent with many arabesques of fast notes played as soft as possible. The main melodies, reflecting Moses speech is reflected softly. The arabesques take the form of either un-measured, cadenza-like fioritures or measured runs or even arpeggiated chords. Strong chordal sections intervene to remind the "judging" feature of G-d. Soft succession of chords, as in bar 55, on the other hand, reflect the reminiscences of days past. A polyphonic section, at bars 163+, reminds us the opening of the first piece. This piece uses a series constructed as a variant of the initial set. This one has more chromatic down steps and instead of the perfect four interval, it features diminished fourths. In the third reading, section or "aliyah" (עליה), "He made them ride upon the high places of the earth" G-d set the Israelites atop the highlands to feast on the yield of the earth and fed them honey, oil, curds, milk, lamb, wheat, and wine.[14] So Israel grew fat and kicked and forsook G-d, incensed G-d with alien things, and sacrificed to demons and no-gods[2]. The piece is built again on a derivative tone-series of the main tone-row. This variant has more major thirds and major seconds and gives the piece a brighter sound-tendency. The pedal tones presented as patterns of repeated notes induce the sense of obsession and abandon. There are several fast and measured sections, as in bars "Vivace", 40+, "Piu mosso", bars:92+, and "Molto animato", bars: 165+, to reflect the abundance and festive life. One particular aspect of the piece is the use of long chromatic runs, not present in the tone-series. As in the "cadenza", bar: 66, ("Piu mosso"). This particular sound-color of the fast chromatic run, is specific to this piece. Also to be noted is the use of those chromatic lines as cluster chord series in bars: 179+. The obsessive repeated notes re-appear at the end. "And the Lord saw this and became angry". G-d saw, was vexed. For they were a treacherous breed, children with no loyalty, who incensed G-d with no-gods, vexed G-d with their idols; thus G-d would incense them with a no-folk and vex them with a nation of fools. A fire flared in G-d’s wrath and burned down to the base of the hills. G-d would sweep misfortunes on them, use His arrows on them: famine, plague, pestilence, and fanged beasts, and with His sword would deal death and terror to young and old alike. G-d might have reduced them to nothing, made their memory cease among men, except for fear of the taunts of their enemies, who might misjudge and conclude that their own hand had prevailed and not G-d’s. For Israel’s enemies were a folk void of sense, lacking in discernment.[15] A long series of chords begins the piece where the chromatic runs, reminders of the previous piece, re-appear but in different forms. A somewhat ambiguous melodic section is starts at bar 40. This section has melodies derived from the original tone-series yet quite different, together with small packs of repeated notes and chord progressions scattered around the keyboard range. No particular tone-series is made for this piece which is based on intervals selected from the previous numbers. In the fifth aliyah, "If they were wise, they would understand this" G-d said that were they wise, they would think about this, and gain insight into their future, for they would recognize that one could not have routed a thousand unless G-d had sold them. They were like Sodom and Gomorrah and their wine was the venom of asps. G-d stored it away to be the basis for G-d’s vengeance and recompense when they should trip, for their day of disaster was near. G-d would vindicate His people and take revenge for G-d’s servants, when their might was gone. God would ask where the enemies’ gods were - they who ate the fat of their offerings and drank their libation wine - let them rise up to help! There was no god beside G-d, who dealt death and gave life, wounded and healed.[15] A lament melody starts on accompaniment figure with "short step up" (as in the Prélude "Des pas sur la neige" by Claude Debussy). A short polyphonic section accedes to wide-range, fast and measured fast notes runs. These runs are compartmentalized with rests of different lengths, bars: 33+. A lengthy part including polyphony, fast runs, melodic developments and chordal successions leads to a dry and staccato section. This expands into a wide dynamic range climax where chordal successions, tone-series based melodies and short and violent chords are all interwoven. The tone-series of the number is characteristic with a balance with half-tone up and down motions as well as sixth and fifth jumps. "For I raise up My hand to heaven, and say, "As I live forever." G-d swore that when He would whet His flashing blade, and lay hand on judgment, He would wreak vengeance on His foes. G-d would make His arrows drunk with blood, as His sword devoured flesh, blood of the slain and the captive from the long-haired enemy chiefs. G-d would avenge the blood of G-d’s servants, wreak vengeance on G-d’s foes, and cleanse the land of G-d’s people.[15] Number six is a strong piece where the melodious sections heard previously are almost absent. Blasts of wide-range notes either as runs or as chord bursts appear throughout. This number's tone-series is somewhat reminiscent of the number two. Even though the intervals are different the up-down motions are similar. "And Moses came and spoke all the words of this song into the ears of the people", the seventh and final aliyah. Moses came, together with Joshua, and recited all this poem to the people. And when Moses finished reciting, he told them to take his warnings to heart and enjoin them upon their children, for it was not a trifling thing but their very life at stake. The first open portion (פתוחה, petuhah)[16] ends here. In the maftir[17] (מפטיר) reading of Deuteronomy 32:48–52 that concludes the Parashah, G-d told Moses to ascend Mount Nebo and view the land of Canaan, for he was to die on the mountain, as his brother Aaron had died on Mount Hor, for they both broke faith with G-d when they struck the rock to produce water in the wilderness of Zin, failing to uphold G-d’s sanctity among the Israelite people. The seventh reading, the second open portion and the Parashah end here.[2] Built on the same tone-series as the first piece and thus concluding the cycle this piece's most noticeable point is the extended melodic development over straight chords. Notes: [1]: The act of proceeding to the reading table in a synagogue for the reading of a portion from the Torah, or the immigration of Jews to Israel, either as individuals or in groups. [2]: A portion of the Torah chanted or read each week in the synagogue on the Sabbath or a selection from such a portion, chanted or read in the synagogue on Mondays, Thursdays, and holy days. [3]: http://www.chabad.org/kids/article_cdo/aid/82432/jewish/What-the-Rebbe-Said-Haazinu.htm "What the Rebbe Said: Ha’azinu" Adapted from the works of the Lubavitcher Rebbe by Malka Touger [4]: Mekhilta is an Aramaic word corresponding to the Hebrew middah, meaning a “measure” or “rule”, in this case referring to certain fixed rules of scriptural exegesis used in halakhic midrash. [5]: Rabbi Ishmael “Ba’al HaBaraita” or Ishmael ben Elisha (90-135 CE, Hebrew: רבי ישמעאל בעל הברייתא) was a Tanna of the 1st and 2nd centuries (third tannaitic generation). A Tanna (plural: Tannaim) is a rabbinic sage whose views are recorded in the Mishnah. [6]: Samuel ben Nahman (Hebrew: שמואל בן נחמן) or Samuel [bar] Nahmani (Hebrew: שמואל [בר] נחמני) was a rabbi of the Talmud, known as an "amora", who lived in the Land of Israel from the beginning of the 3rd century until the beginning of the 4th century. Amoraim; "those who say" or "those who speak over the people", or "spokesmen"), were renowned Jewish scholars who "said" or "told over" the teachings of the Oral Torah, from about 200 to 500 CE in Babylonia and the Land of Israel. [7]: Abba ben Joseph bar Ḥama (c. 280 – 352 CE), exclusively referred to in the Talmud by the name Rava (רבא). A fourth-generation rabbi "Amora" who lived in Mahoza, a suburb of Ctesiphon, the capital of Babylonia. He is one of the most often-cited rabbis in the Talmud. [8]: Easton's 1897 Bible Dictionary. Retrieved April 23, 2015, from Dictionary.com website: http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/dew [9]: Classical Jewish legal Biblical exegesis, based on the biblical books of Bamidbar (Numbers) and Devarim (Deuteronomy). [10]: http://www.chabad.org, "Torah Reading for Haazinu" with Rashi's commentaries [11]: The entire body of Jewish law and tradition comprising the laws of the Bible, the oral law as transcribed in the legal portion of the Talmud, and subsequent legal codes amending or modifying traditional precepts to conform to contemporary conditions. [12]: A liturgical prayer consisting of all or part of Psalms 113–118, recited on Passover, Shavuoth, Sukkoth, Hanukkah, and Rosh Hodesh. [13]: http://etzion.org.il/vbm/english/parsha/51haazin.htm, used by permission [14]: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Haazinu [15]: http://www.chabad.org, "Torah Reading for Haazinu" with Rashi's commentaries [16]: An open parashah (a section of a book in the Hebrew text of the Tanakh), set apart in roughly the same way as a paragraph would be in modern text. [17]: Maftir (Hebrew: "concluder") refers to the last person called up to the Torah on Shabbat and holiday mornings: this person also reads the haftarah portion from a related section of the Nevi'im (prophetic books).

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||