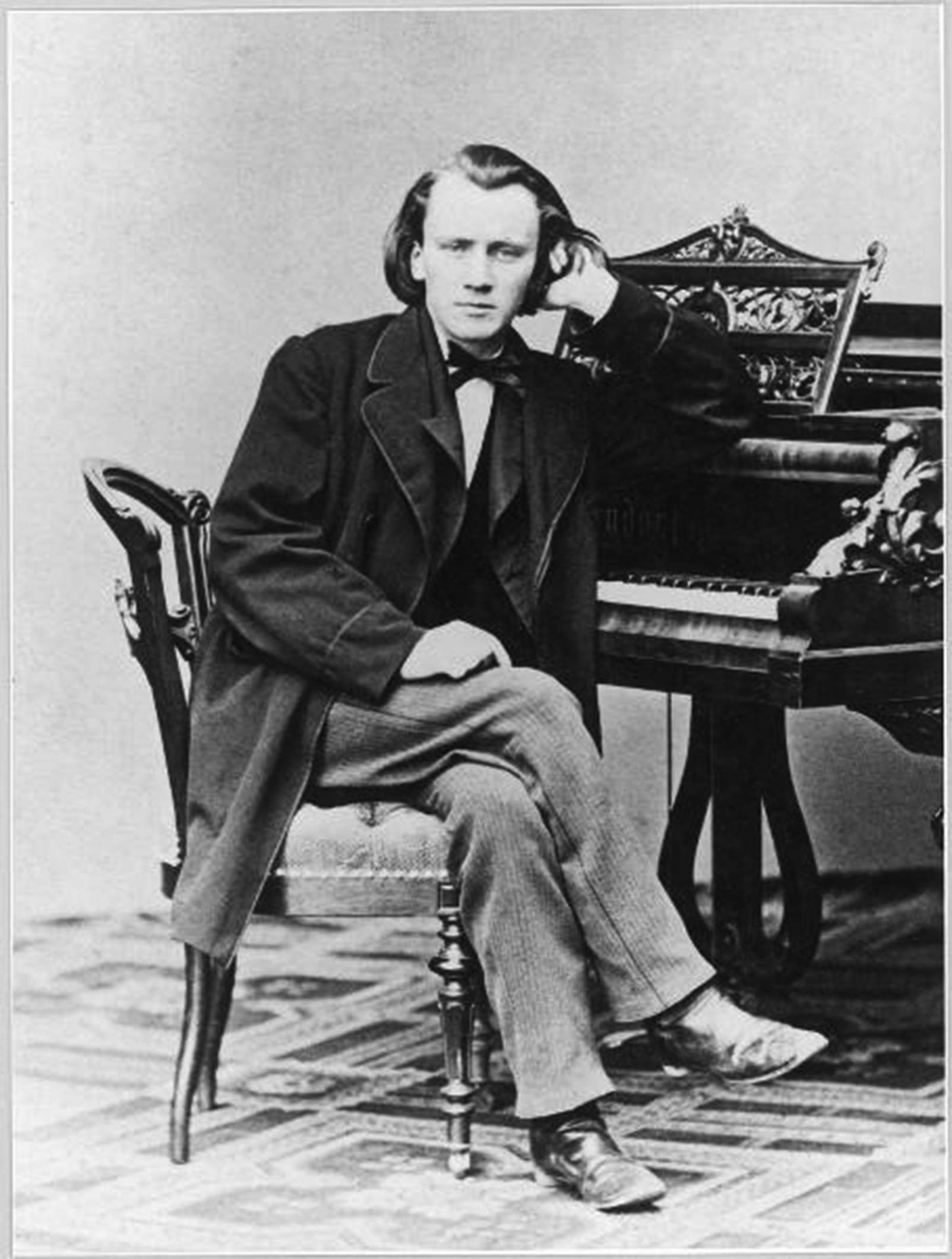

Johannes Brahms (1833-1897)

The Piano Sonata N.3 in F minor op.5 and Four Ballades op.10

|

Brahms Piano Sonatas Even though they may seem the continuation of the late style of Beethoven, the three Sonatas by Brahms, composed between 1851 and 1854 display an amazing, genuine individuality. At the age of 20, the composer embarks in this monumental musical form, injects in it his strong individuality and then, he leaves the "piano sonata" form for ever. Right from opus one, where the manuscript title reads "Fourth Sonata", Brahms will inject in this majestic beethovenian form a fully romantic breath of life. The images of the North Germany, cherished by the composer will show up straight away. All three Sonatas display a clear connection with the symphonic, orchestral way of thinking music. Schumann, when he meets Brahms in 1853, will notice that first. He would write in his famous article published in the NeueZeitschrift für Musik: "He (Brahms) transforms the piano into an orchestra with exulting and moaning voices. Those are the Sonatas or, rather, disguised symphonies .." Apart from their orchestral ecriture, the three Sonatas have other common aspects. A personal layout of the classical form, slow movements more or less like variations in the choral style, "cyclic-form"-like connections between movements, richness of the contrapuntal craft, the extend of the development sections. Piano Sonata N.3 in F Minor op.5 With this work, dedicated to the Comtesse Ida von Hohental, Brahms leaves the piano-sonata form to never return to it The second and fourth movements were composed first, in the summer of 1853, the remaining ones during the fall of the same year, he was just 20. It is the only composition Brahms showed to Schumann during its elaboration. Commentators discerned a kind of self-portrait in it and it is very diversified in its integrity. Brahms displays a very well-established personal style. Five movements, instead of the usual four in the classical sonata, a cyclical, symphonic-poem like setting and a compact ecriture relying heavily on block chords, disregarding any "light" embellishments which are typical of the piano ecriture of the epoch are some of its striking aspects. Interestingly, a similar ecriture will also show up in his most late works particularly the Clarinet (or Viola) Sonata op.120 and partly in his piano pieces op.119. I. Allegro maestoso The evolution of the composer, in just a year, since the Sonata op.2 is admirably shown here. The exposition of the first theme, spread in four rhythmical variations over a span of 38 bars displays a rare concentration of ideas. The first "cell" explodes as a lightning over a chromatically descending bass line, as in a Passacaglia, the same idea is then re-exposed, softly over a repeated triplets figure in the bass as with the German Requiem ("A German Requiem, To Words of the Holy Scriptures", Op. 45) after a furious repeat of the first idea, the calmer variation of the motive is presented in augmentation with strong block-chords ("Fest und bestimmt"). The second theme, somewhat a la Chopin in its presentation in A-flat major is very modulating and connects to the third one, heavily chromatic over a pedal tone of A-flat. All that material is extracted from the first musical idea through "Liszt-ian" procedures. In the development, an alluring line appears on the left hand, "quasi cello solo". The Coda is more animated (Piu animato) some of its elements announce the Scherzo of the Fourth Symphony. II. Andante espressivo Brahms composed this page first and put as an epigraph those verses from the poet C. O. Sternau (the pseudonym of Otto Inkermann) on top of it: Der Abend dämmert, das Mondlicht scheint, da sind zwei Herzen in Liebe vereint und halten sich selig umfangen Through evening's shade, the pale moon gleams While rapt in love's ecstatic dreams Two hearts are fondly beating. This vast "nocturne" of intense poetic content, is one of the most beautiful "love scenes" in the German romantic piano literature. It is in the line of the slow movement of the Pathetique Sonata by Beethoven (same tonality) and of the Second Symphony by Schumann. In the first part, an often thematic construct procedure by Brahms can be seen. It is a motive with descending thirds, often used by the composer, for example in the Intermezzo op. 119 N.1. The following "duet" with melodies at both hands unmistakably depicts "two lowers in the moonlight". The next section, Poco piu lento in D-flat major, where both hands respond to each other with a line fragmented between them and played with double sixths, will raise to a climax of ecstasy. The third section, Andante molto in D-flat major will bring a sublimated paroxysm of love only found elsewhere in Richard Strauss late operas' love scenes. It not unreasonable to think that Wagner who have heard the Sonata in 1863, remembered it when composing "Der Vogel der da sang.." in the second act of his Meistersingers. A few bars long Coda, restating the first theme, will conclude that enchanting movement. III. Scherzo: Allegro energico According to Clara Schumann this movement evokes a cataclysm. There is actually a kind of "darkness" in this demoniacal waltz at Allegro energico. Its chopped, jerky theme may remind Liszt. However, the serene Trio in D-flat major, in total contrast, may recall the previous Andante. IV. Intermezzo (Rückblick - "A look back") This "look back" is a macabre reminiscence of the Andante. The Andante's beautifully serene theme is now in B-flat minor and is sustained by anxious repeated note triplets at the left hand evocative of a soft timpani part. All together the "romance" theme of the Andante is here transformed into a kind of Funeral march it is a really pessimistic vision of love. V. Finale: Allegro moderato ma rubato A free-form Rondo, it seems to be built on the Beethovenian idea of a victory won after a thorough hardship. Starting in the low and dark ranges it makes its way to brightness and glory. The first theme (Allegro moderato ma rubato), remind us the torments of the preceding Intermezzo, it starts painfully its march to the "victory". The second theme, in F-major, very lyrical employs partly the idea of the bright choral theme of the first movement but this time over an accompaniment of undulating left hand arpeggios and tremolos. The first notes which makes for that theme: F - A - E, strangely states a motto used by the violinist Joseph Joachim: "Frei, aber einsam" (free but alone). The second couplet of this "quasi Rondo", in D-flat major, is a hymn-like homophonic theme which will expand and raise all through. This theme will then change to provide material for the upcoming Piu mosso and Presto sections. Those sections, always faster, bring a grandiose Coda which concludes this monumental work in a majestic way. Four Ballades op.10 Originally, the musical "Ballade" is inspired by Anglo-Saxon literary sources. Those poems draw from legend-like sources and develop them in romantic settings. Poets like Herder, Goethe, Schiller and Uhland are representative of this "Sturm und Drang", literally "storm and drive" or "storm and urge" movement. Conventionally translated as "storm and stress", it is a proto-Romantic movement in the German literature and music that took place from the late 1760s to the early 1780s. Individual subjectivity and, in particular, extremes of emotion were given free expression in reaction to the perceived constraints of rationalism imposed by the Enlightenment and associated aesthetic movements. The period is named for Friedrich Maximilian Klinger's play Sturm und Drang, which was first performed by Abel Seyler's famed theatrical company in 1777. [from Wikipedia] Put into music by Zelter, Neefe, Zumsteeg and mostly Loewe, the "Ballade" is very strong in the Opera field too. Since the "Ballade of Senta" in "The Flying Dutchman" by Richard Wagner, a legendary ghost ship that can never make port and is doomed to sail the oceans forever; the Ballade will be strongly present in Chopin's piano music. The Four Ballades op.10 are the only inclusion of literary sources in the music by Brahms. In the spring of 1854, the composer discovers a folkloric compilation: the "Stimmen der Wolker" by Herder which includes the poem "Edward" previously set to music by Schubert and Loewe. It is a very old Scottish text that Brahms will process in a very dramatic way, almost as a melodrama. While the poem which narrates a parricide is strongly connected to the first piece, it, nevertheless, influences the entire work. The main characteristic of those pieces is that they do not have a proper melodic development. The motives are exposed, connected without any elaboration of the "ecriture", almost in a "naive" way which fits perfectly the orally transmitted legends based literary style. I. D Minor: Andante The atmosphere of the old legends of the North is striking. It is a dialogue between the mother and her son. A "page of strange novelty" according to Robert Schumann. The first section sets the background, bars: 1 - 8. The mother: "Why your sword is so blood-red, Edward, Edward?" Poco piu mosso, bars 9 - 13. Edward: "Oh I killed by falcon, mother, mother!" Tempo I, bars 14 - 21. The mother: "The blood of the falcon is not that red, Edward, Edward!" Poco piu mosso, bars 22 - 26. Edward: "Oh! I killed my ginger haired horse, mother, mother!" In the second section, Allegro ma non troppo, bars: 27 - 60, the crime is narrated with Beethovenian triplets. The mother: "Your horse was old, you did not need to do that, Edward, Edward! Another unbearable crime is oppressing you, Edward, Edward!" Edward: "Oh! I killed my father. Oh! My hart aches!" The second part of this section, bars 45 - 60 depicts the malediction of Edward. "My foot will never stand on the ground. Mother! I leave you with my malediction and with the flames of the underworld, Mother! Because you made me do it!" The last part, Tempo primo, paints the lamentations of the mother. II. D Major: Andante The second Ballade is in strong contrast with the preceding one. Structured as A B C B A, it deploys three distinct themes. The first one is like a "chanson de jeste" (an epic lyric) like melody. Both naive and tragic at the same time. The second theme, B, is brisk and jerky in B minor while the third one, C, offers a strange pianistic ecriture where each note comes with an appoggiatura (accaciatura) not unlike some pieces by Schumann. III. B Minor: Intermezzo: Allegro This third "Ballade" in B minor keeps, even with its leaping and slender ecriture a dark and threatening character and remains in the context. The central part, Trio in F-sharp major, with its delicate sonorities evolves in high ranges and remains pianissimo and "ppp" all the time. Robert Schumann relates: "a demoniacal page of real splendor". IV. B Major: Andante con moto Somehow more distant from the preceding ones this last Ballade evokes the latest piano pieces of the composer. A very elegant ecriture and the minor - major shifting in the first bars is almost like some Gabriel Faure. "In what marvelous way, the melody hesitates between minor and major and finally remains lugubriously in major" wrote Schumann. The middle section in F-sharp major: "col intimissimo sentimento, ma senza troppo marcare la melodia" (with the most intimate feeling but without pointing out too much the melody), presents a blurry theme wrapped with a dense accompaniment playing two against three at both hands. Each main section is stated twice in a raising misty atmosphere. |

|||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||

|